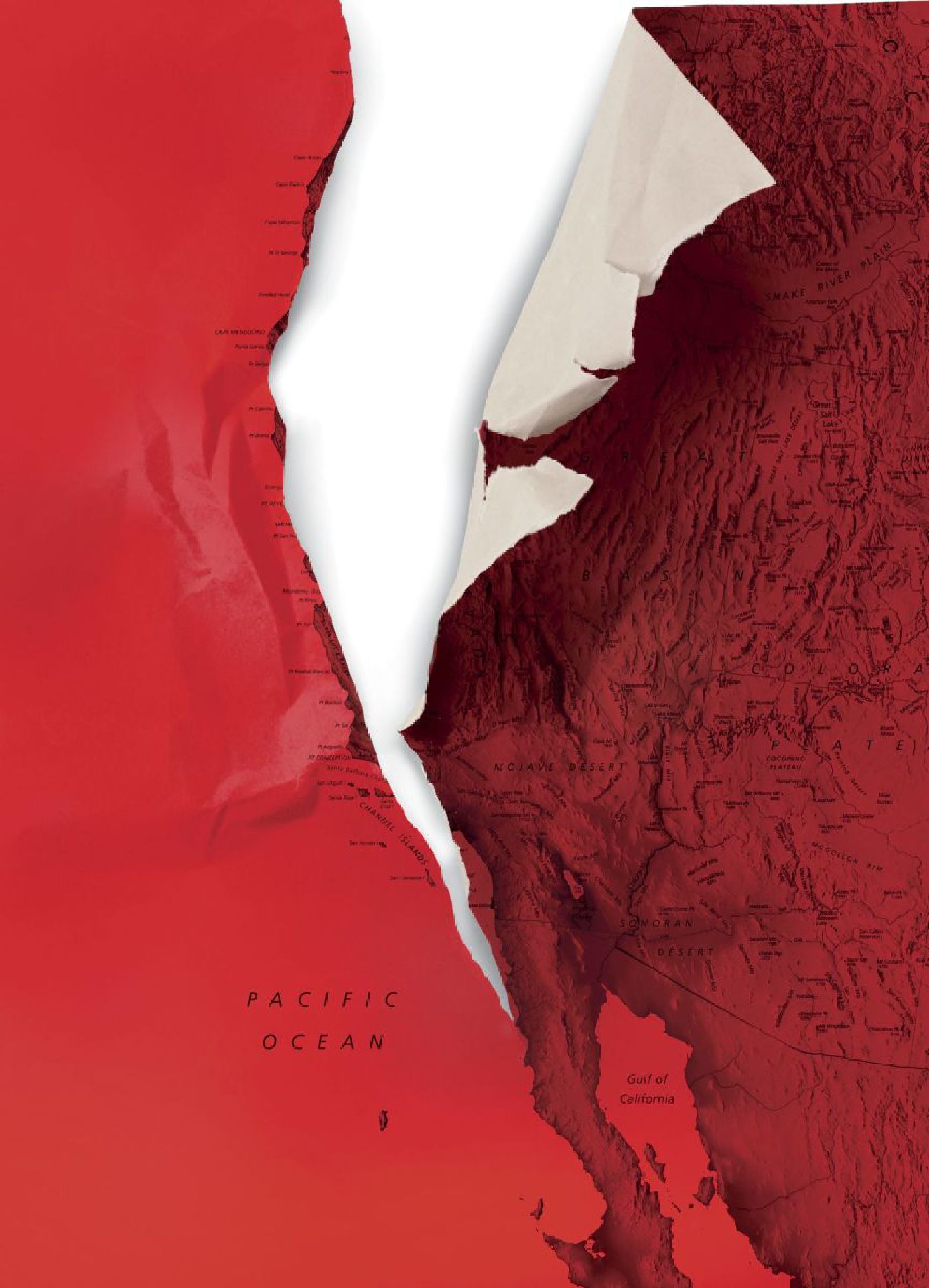

The Really Big One by Kathryn Schulz is a scientific article which discusses the incredibly high likelihood that a disastrous earthquake will hit the Pacific Northwest in the near future. It analyzes a number of statistics on just how impactful this earthquake and the resulting tsunami will be, using a number of anecdotes and easily understood examples accompanied by a somewhat casual writing style to make itself more appealing and comprehensible. The information it provides is more than just digestible - it is terrifying. The grim descriptions of this natural disaster and the unbelievable aftermath it will leave behind are meant to scare the audience and motivate them to act - either to take preventative measures against this impending calamity or to stay as far away as possible.

Among the many examples Schulz uses to make her article more understandable is her comparison between hands and tectonic plates. She instructs the reader to manipulate their hands in a number of ways to simulate the interaction between tectonic plates, and then goes on to have the reader physically simulate the interactions that would cause a devastating earthquake, saying, “If, on that occasion, only the southern part of the Cascadia subduction zone gives way—your first two fingers, say—the magnitude of the resulting quake will be somewhere between 8.0 and 8.6. That’s the big one. If the entire zone gives way at once, an event that seismologists call a full-margin rupture, the magnitude will be somewhere between 8.7 and 9.2. That’s the very big one.” (Schulz) She then goes on to cite Kenneth Murphy, the director of, “FEMA’s Region X, the division responsible for Oregon, Washington, Idaho, and Alaska,” who says that, “‘Our operating assumption is that everything west of Interstate 5 will be toast,’” (Schulz) in order to express how utterly devastating the earthquake the reader had just imitated will be. By using these very easily